Vorticism and its Discontents

The Vorticists: Manifesto for a Modern World is currently on exhibition at Tate Britain until 4 September 2011.

After the self-assured swings of Post-Impressionism, Cubism and Futurism in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, came a more obscure, ambiguous ism. A poetic term invented by a poet, the word Vorticism, established by Ezra Pound in 1914, is itself an uncertain one. According to the Tate’s accompanying exhibition catalogue, Vorticism ‘forged [art] for a changing world.’ Born in an age of mechanical reproduction, Vorticism clashed with a time of universal socio-political upheaval and what was then the Great War; one of the most crippling cultural shocks to the twentieth century nervous system.

Soon after Pound founded Vorticism in 1914, painter and writer Percy Wyndham Lewis avowed himself the leader of the movement, affirming his authority with the début of experimental cultural journal, Blast. True to the promise of its title, Blast was bombastic on the inside as well as outside. An in-your-face, shout-out-loud magazine with a fuchsia pink cover, Blast served as an unofficial alternative manifesto of Vorticism, its beliefs and ideas splashed across its pages violently like paint, both glorifying British civilisation and bemoaning its discontents. The pages of the first and second issues, laid bare in the exhibition, reveal a collusion of “blastings” and “blessings”, ambiguities and attitudes foreshadowing the ‘changing world’; the future of which, like Wyndham Lewis’ paintings with their perpendicular lines and jagged angles, remained scrambled and unclear.

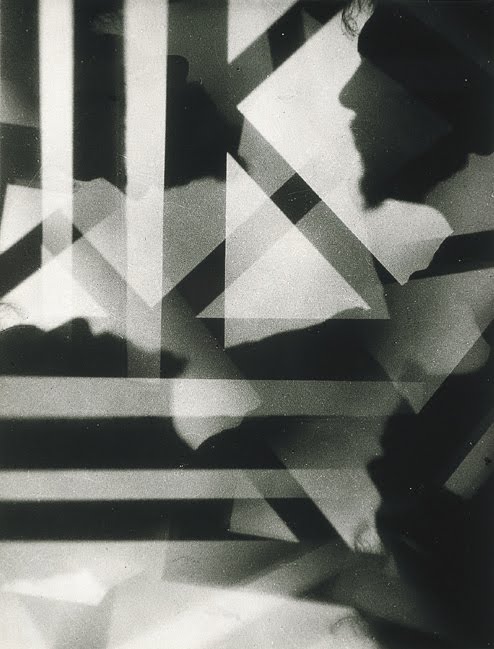

Vorticism surfed on the brink of such a world, weighted down by the ideas of the past and the trinity of isms that came before, and simultaneously revolutionised by the newness of technology (as evident in the print and photography on exhibition). Indeed, the breadth of the exhibition emulates the anxieties of the era as distinct gulfs begin to appear between artworks. Paintings with muted colour hang next to dramatic canvases of monochrome. Jacob Epstein’s paperweight-sized objects sit amid angular artworks, in sight of room-filling sculpture. Alvin Langdon Coburn’s soft focus, camera obscura photographs share a room with hastily penned sketches. These contradictions draw a vague picture of ‘a changing world’ in which the idea of change is heftier and more terrifying than the change itself. Amid the rubble of such conflicting ideas, generated by what Virginia Woolf termed in The Years an ‘uncertain’ era, it seems only natural that Vorticism was short-lived. A movement that really was a movement, Vorticism lasted just four years; a fleeting aesthetic strain which began to trace uncertain blueprints of a similarly uncertain future.

As it manoeuvres in a linear, geographic sequence through seven sections – occasionally flitting from London to New York and back again, charting Vorticism’s beginnings in London with a look at Modern art between 1912 and 1914, through to New York’s Penguin Club in 1917, and back to London’s Camera Club in the same year – the exhibition has an apparently clear sense of direction. However, like the period from which Vorticism pieced itself together, the exhibition is irrevocably confused. The amalgamation of sketches, paintings, photography, sculpture and literature – with manuscripts from soldiers’ censored letters to home-based sweethearts, excerpts of Blast, to The Waste Land – produce the effect of there being too much and yet all too little. Coburn’s haunting kaleidoscope portraits of Pound, Eliot’s athletic prose and Epstein’s futuristic, angular sculpture get lost somewhere in the excess of the time and its ‘heap of broken images’. Vorticism is exhibited here as in an aesthetic waste land, the rubble of ‘forged’ efforts and ideas that strive to write and paint the future, but cannot. Perhaps the perennial dilemma of Vorticism rests in its ‘forged’ nature as art that is consciously trying too hard to loose itself from its past, while it can only anticipate its future.

Still, there is beauty in the disillusionment. There is something profoundly poetic in Vorticism’s ability to posture ideas but not to see them through as such; as a body of work that appears unfinished but is really, as Leonardo da Vinci once wrote of art wrongly deemed incomplete, abandoned. Meanwhile, the exhibition alerts us to another great war, fought at home, between technology and culture, the artworks interacting in a kind of battle with each other. As Coburn once said of his photography, ‘[t]hink of the joy of doing something which it would be impossible to classify, or to tell which was the top and which the bottom!’ It is only this kind of joy one can take from the Tate Britain’s Vorticism exhibition: it is a beautiful mess. Vorticism is shown here, in orderly disorder, to represent the discontents of a select generation of poets and painters who couldn’t control the world – as neither, the exhibition reminds us, can we.